Most entrepreneurs sweat over their slide deck.

Adam Neumann strolled into the boardroom barefoot, and walked out with one of the biggest cheques of his career.

No revenue or users. Just a (questionable) reputation - wrapped in a narrative so tightly spun it made the numbers irrelevant.

And when it came to pitching, Andreessen Horowitz didn’t blink. They made Flow their biggest single investment. Bigger than Airbnb. Bigger than Facebook.

Which raises the question: If almost half a billion can land without a product, what makes investors reach for the pen?

I’ve spent years helping people prep for raises - and most of them still think “proof” is the magic word. Apparently it’s “Neumann”.

Turns out, the right story, told by the right person, can look like a calculated play instead of a gamble.

Tempted to fake it until you fund it? Careful.

Neumann didn’t actually fake anything; he reframed failure as foresight. And in doing so, reminded everyone that charisma is still legal tender in Silicon Valley.

Here's how he outplayed the table.

A lesson in turning collapse into capital

After WeWork’s spectacular implosion, people thought Neumann would keep a low profile. And he did… if your definition of low profile includes parading through interviews, packing out panel appearances and working the VC circuit like a headline act.

It was a full-throttle return. Each appearance chipped away at the image of a reckless founder and rebuilt him as a battle-tested operator.

The WeWork collapse was reframed as a lesson in hyper-growth; education you couldn’t buy and experience at a scale most founders never touch. The more visible he became, the more the story shifted from downfall to masterclass.

By the time Flow emerged, the groundwork was set. Neumann had positioned himself not as a risk, but someone who’d already survived the highest-stakes version of the game.

So when a16z backed him again, it felt like the logical next step. The narrative had done its job.

So what do you pitch when there’s nothing to pitch?

A story. A thesis. A half-built future.

When Flow raised that hefty investment, there was no product in the traditional sense.

But Neumann didn’t walk in empty-handed.

He led with the asset base. Flow had already quietly acquired around 3,000 rental units across Atlanta, Miami and Nashville. These properties were his prototypes. A kind of stealth-mode REIT, branded under Flow and operating as a tangible beta.

But more than that, he had orchestrated a grand vision for modern living (conveniently in the buildings he owned).

It was essentially WeWork’s community model with a fresh coat of paint: not just for office life, but for everyday life. And somehow, after bankrupting the office version - he passed off the rerun as innovation.

Post-COVID, with remote work unshackling people from cities and offices, “housing as a lifestyle platform” suddenly sounded visionary again - especially to younger professionals watching property prices sprint while their wages crawl.

For many, a curated, community-driven rental felt less like settling for less and more like sidestepping the housing market altogether; a way to buy into connection, amenities and a better standard of living without the decades-long mortgage hangover.

That’s exactly what Flow packaged into its pitch:

Housing that included wellness spaces, work zones and community hubs

A residential experience that felt curated, not commoditised

The promise of belonging, not just a lease

(As far as sales pitches go, this one had me - as a wellness advocate - mentally moving in).

No one was calling it a utopia, but the demand was clear: people wanted community baked into their rent.

And then came the toilet plunger…

Neumann, in full Neumann mode, contrasted renters with homeowners using a characteristically weird-but-effective metaphor: owners reach for the plunger themselves; renters call someone else.

Flow, he claimed, would blur that distinction - shaping more proactive, invested tenants through a novel “value-sharing mechanism” that mimicked the psychology of ownership.

Translate that into numbers and you get: lower churn, higher NOI and a behavioural shift at scale.

For investors, that meant fewer empty units and income that was easier to forecast. And Andreessen didn’t need much persuading, anyway. To him, Flow addressed something far more human than housing: the drift people feel when they lack roots or connection.

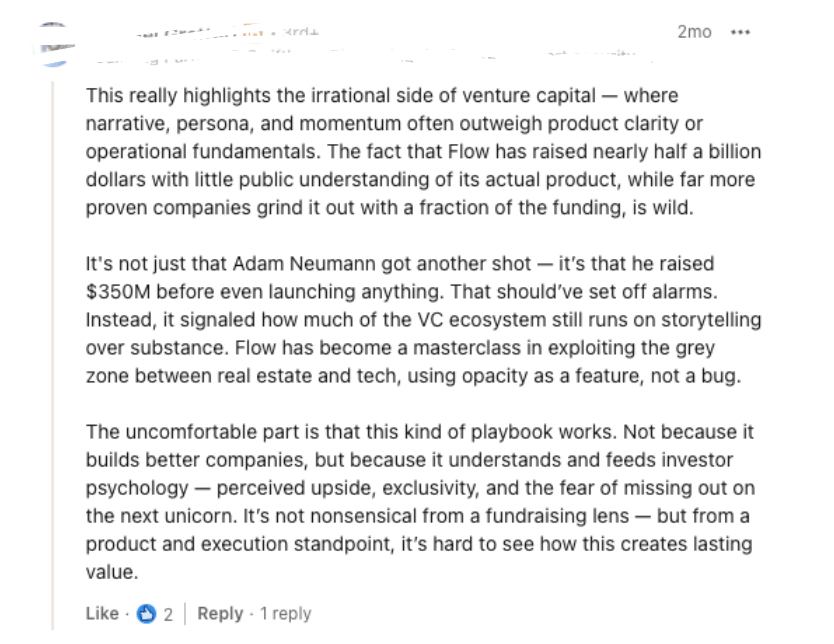

Ultimately, Flow became the belief that people would pay to feel anchored, especially if you made it look like ownership. Not everyone found that comforting, however - with one commenter on my recent LinkedIn post explaining:

“This really highlights the irrational side of venture capital - where narrative, persona and momentum often outweigh product clarity or operational fundamentals. The fact that Flow has raised nearly half a billion dollars with little public understanding of its actual product, while far more proven companies grind it out with a fraction of the funding, is wild”.

To sum up what they’re saying: in VC land, conviction often cashes out faster than clarity.

Remind me again, how the hell did he pull this off?!

By playing industries against each other - and giving each what they wanted.

Flow positioned itself as the future of renting: part community platform, part property play, part fintech. A little WeWork, a little Blackstone, a little Stripe.

And crucially, it sat neatly in the gap between two industries that rarely speak the same language: real estate and tech. Neumann turned that gap into leverage.

Flow has become a masterclass in exploiting the grey zone between real estate and tech - using opacity as a feature.

In that grey zone, both sides saw what they wanted:

> Real estate investors saw a tech moat

> Tech VCs saw asset backing

Neither side could fully interrogate the other, and neither truly understood the other.

The real trick was that he wrapped high-risk vision in low-risk structure. Flow already owned 3,000 cash-flowing rentals - and to lenders, this wasn’t a tech punt, but a functioning portfolio with room to grow.

That’s exactly where the illusion landed. Tech pulled one way: audacious, high-growth, world-shaping. Real estate pulled the other: stable, familiar, low-volatility, predictable.

Blended, it dulled risk and lit up every investor hot button. Committees didn’t see “too risky”, they saw “maybe this is that rare high-return, low-risk play”.

But is it…?

Rarely. But framing is everything.

Just look at The Wing: a women-focused co-working and social club that raised millions, scaled into major U.S. cities yet still shuttered operations when luxury leases and member churn shredded the margins.

If you ask me, that kind of mismatch kills more companies than bad ideas ever do.

Bottom line: Flow didn’t have a product. But it had a portfolio. A category-crossing thesis. And on top of that, a genius founder who’d already turned philosophy into infrastructure.

What you should take from this (despite a deep breath)

Flow’s product was never housing - it was all Adam. The narrative replaced the business model entirely. And that worked, not because the fundamentals were strong, but because everything around them was engineered for belief.

In my opinion, he played a blinder. But bear in mind there are a few other things made that possible:

Timing | Audience | Reputation | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

In a jittery market still chasing breakout bets, boldness has gravity. Subtle doesn’t raise headlines - or rounds | Neumann wasn’t cold-pitching strangers. He returned to VCs who’d already backed him. That kind of muscle memory shortens the trust cycle | Controversial? Yes. But familiar. And familiarity, in fundraising, often outranks clarity | Flow de-risked the deal by combining high-risk founder narrative with low-risk, income-generating assets, creating just enough comfort for both sides of the table |

It also didn’t hurt that Marc Andreessen had backed WeWork. Doubling down on Neumann gave him a chance to rewrite that chapter - which makes this less “belief in a founder” and more reputational ROI.

Here’s the caveat: if your name doesn’t carry weight in Sand Hill, you don’t get to walk in pre-product, post-implosion and ask for a clean slate. You’ll need something tighter. A story that doesn’t just explain what you’re building, but why now, why you and why it’s not just another solution in search of a problem.

Too good to gate keep

On a less mind-bending note… I want you to know me as well as my pitch analysis - and, frankly, my impeccable taste in music.

My favourite song of all time is 23 by Jimmy Eat World. It’s cold and distant, but somehow hopeful - like an 1880s synth fight, if that makes any sense.

It fills me with this strange, stubborn optimism. I’m already a motivated person; I don’t usually need a soundtrack to get moving. This song, though… it lights the fuse.

Trust me, it’s well worth 8 minutes of your time.

If you do one thing this week, do this:

Know your mission well enough to make anyone care. That’s the bridge between passion and buy-in.

If you can’t explain it clearly, you can’t sell it. And if you can’t sell it, you can’t expect people to back it. Belief moves you forward; a mission people can rally around moves everything faster.

You’re in too deep to stop reading now…

What stuck with me, reading up on Flow, wasn’t the scale of the raise. It was how Neumann made a high-risk play feel like a safe bet. Like him or not, that’s some world-class deal-making - and I’ll admit, I’m impressed.

If you’re mid-fundraise (or plotting one) and want to talk structure, story or both - just reply. Can’t promise you a $450M investment, though.

Till next time,

James