Sugar is everywhere. It’s in cereal, bread, “healthy” granola bars, pasta sauces and probably the air at this point.

At some point we stopped treating it like a treat and started designing entire diets around it. It’s baked into convenience, habit and routine - so much so that avoiding it now feels like a lifestyle choice, not a preference.

But it wasn’t always like this. In fact, there was a time when people genuinely believed sugar - and flavour in general - was a moral threat.

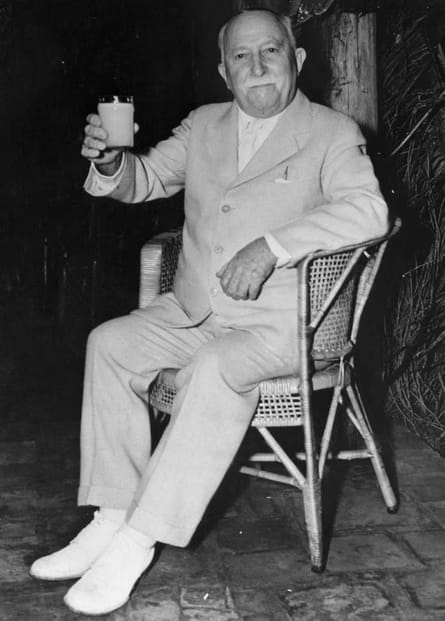

And leading the charge on that crusade was John Harvey (J.H.) Kellogg: doctor, wellness fanatic and the man who invented corn flakes specifically to stop people from enjoying themselves.

He created the cereal as a bland, behaviour-correcting “health food”. Guests at his sanitarium loved it because it was the only thing on the menu that didn’t taste like punishment. Demand was massive, but he refused to commercialise it.

Meanwhile, his younger brother Will Keith (W.K.) Kellogg watched all of this unfold and noticed that:

people kept buying the cereal

production costs were predictable

America was shifting toward convenience

and, controversially, humans enjoy flavour

It was product-market fit before the term even existed.

While J.H. protected society from sugar and sinning, W.K. acted like a rational adult.

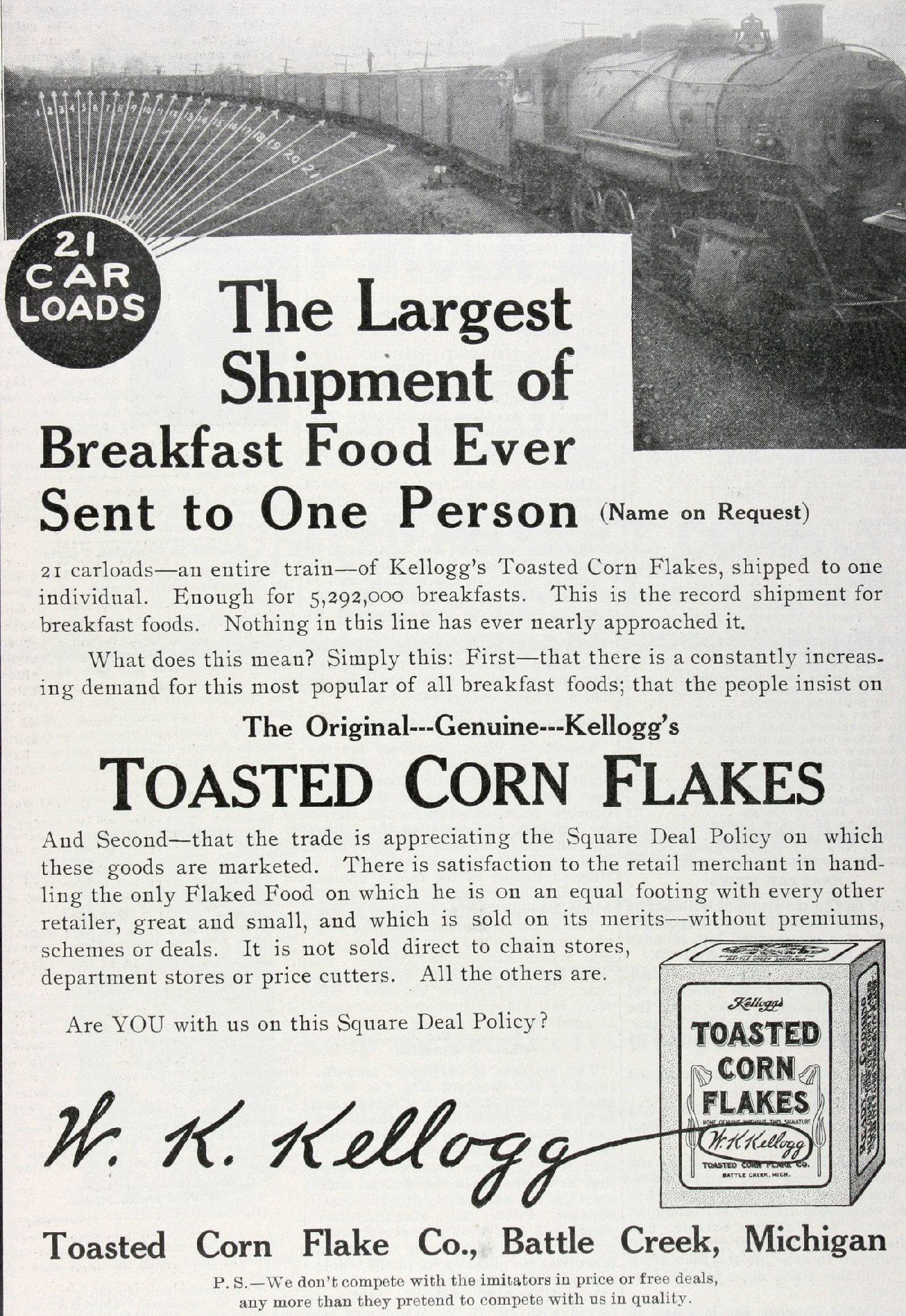

He raised capital, bought proper equipment, scaled production and turned a moral lecture into a mass-market staple.

A cereal created to prevent temptation became one of the most commercially irresistible products in American history.

The irony writes itself.

And breakfast? Permanently changed - from cooked meals to cupboard food.

Stick with me - buried in this family feud are a few capital-raise lessons worth stealing.

TL;DR

Only here for the highlights? Here’s what you need to know:

1/ Corn flakes started as a bland “morality food”, but W.K. Kellogg spotted the real opportunity his brother ignored - proven demand plus perfect timing for convenience eating.

2/ He commercialised what worked, adapted the product to what customers actually wanted and used early brand building to unlock the mass market.

3/ His capital raise wasn’t for experimentation - it removed bottlenecks: manufacturing, distribution and marketing.

4/ The business compounded for decades, went public, split and eventually sold in pieces for nearly $40B.

5/ The lesson → proof beats ideology, small product tweaks can expand your TAM and capital should scale what’s already working, not fund guesses.

The bizarre moral logic that launched a cereal empire

To understand why Kellogg’s became Kellogg’s, you have to look at the very peculiar world it was born into.

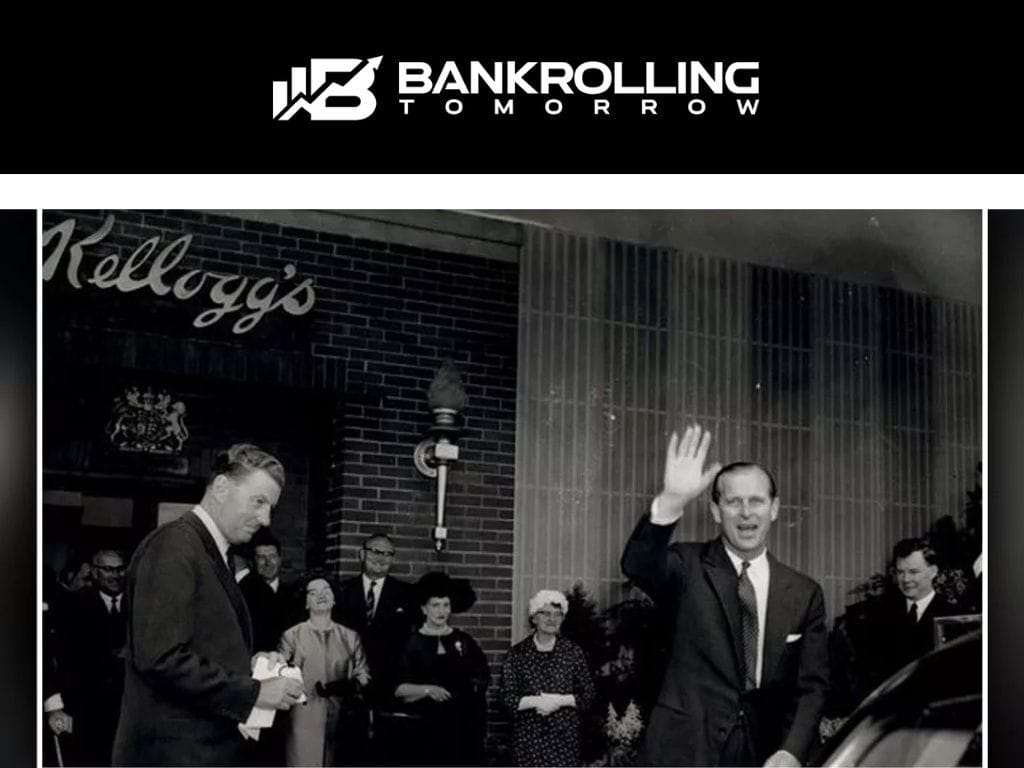

J.H. Kellogg was a doctor who also just happened to run America’s biggest wellness spa, the Battle Creek Sanitarium, long before wellness became a $5 trillion industry. It was here that he invented corn flakes as a bland, corrective, “moral” health food, designed to stop patients from falling victim to the temptations of flavour.

The rationale wasn’t rational at all:

food = pleasure, pleasure = sin, therefore flavour = spiritual bankruptcy

And yet, the cereal was a hit. Not because it tasted good, but because it was the only thing on the menu that didn’t feel like repentance.

Guests took boxes home. Demand grew naturally. But J.H. point-blank refused the idea of taking his cereal to the market.

Scaling it would’ve meant making it palatable - i.e., adding sugar - and that clashed with his mission to keep breakfast as joyless as possible.

So he blocked every attempt to take it beyond the sanitarium walls.

The rest of America headed in the opposite direction, however

Industrial foods were taking off, grocery stores were multiplying and households were embracing convenience eating.

A national debate emerged about what a ‘proper’ breakfast should look like - and for once, everyone agreed: quick, easy and preferably not fried in bacon grease.

(For the record, I’m also a big fan of convenience, but instead of reaching for a bowl of cornflakes, I’m downing raw eggs. Sounds unhinged, but apparently it’s healthy).

Anyway - questionable breakfast choices aside - the changing market and exploding demand were exactly what W.K. Kellogg (the “sinful” brother) knew how to capitalise on.

So to convert proven demand into a consumer brand, he filed the Kellogg trademark, broke away from his brother’s purity project and started building the Kellogg’s we know and love feel neutral about today.

How Kellogg’s “changed breakfast forever”

Once W.K. stopped waiting for his brother to realise flavour isn’t a moral hazard, things finally started moving.

In 1906, he did what every sane founder eventually has to do: he raised capital with a clear purpose. Not for “exploration”, not for “product vision sessions”, but to actually make corn flakes at scale - machinery, factories, distribution, the whole boring-but-essential backbone.

And the second the cereal escaped the sanitarium, it took off.

W.K. went all-in on the playbook his brother hated: national advertising, upgraded packaging, early mascots, coupons. Basically everything J.H. considered spiritually corrupt. Which, of course, is why it worked.

The best part? Kellogg’s grew through consistency over hype; the trait no one brags about on LinkedIn but everyone wishes they had.

For 46 straight years, the company just kept going. Steady margins, steady expansion, steady everything.

By the time they IPO’d in 1952, Kellogg’s wasn’t just a cereal company, but the cereal company. The breakfast aisle basically revolved around them.

And the compounding didn’t stop.

Jump to modern day:

2023: Kellogg’s splits into two public companies - Kellanova and W.K. Kellogg Co.

2024: both get acquired.

Mars buys Kellanova for $35.9B.

Ferrero buys W.K. Kellogg Co for $3.1B.

Nearly $40 billion in combined value… from a product originally designed to stop people sinning before lunchtime.

Honestly, you couldn’t script a better punchline.

If cereal can teach you strategy, this is it

Regardless of how you feel about sweetening your breakfast, there’s a thing or two you can learn from the Kellogg brothers.

A) Prove demand before you can pitch

If you want a pure example of proven demand, Kellogg’s is it.

W.K.’s biggest advantage wasn’t a grand vision; it was the fact that people were already buying the cereal long before he raised a dime. Years of accidental A/B testing at the sanitarium gave him something most founders lack: real behaviour, rather than the hopeful projections that usually end up in pitch decks.

If you want investors to lean in, don’t give them a fantasy; give them evidence. Even tiny signals - repeat orders, waitlists, people coming back without discounts - beat the prettiest deck. Demand is your only real leverage.

B) Adapt your product to what the market actually wants

J.H. refused to add sugar because it violated his worldview. W.K. added it and built a breakfast empire.

This sparks an age-old entrepreneurial dilemma:

Do you protect your belief system so tightly that the business suffocates… or adjust the product enough that customers actually buy it?

My view = founders who evolve survive. Founders who fight customer preference often end up writing medium posts about “why the world wasn’t ready for their vision.”

C) Raise capital to remove bottlenecks (not to explore your imagination)

Capital should scale what’s already working.

When W.K. raised money in 1906, it wasn’t for exploration, iteration or whatever innovation buzzword founders throw around when they aren’t sure what to do. He already knew the cereal worked.

The capital went straight into machinery, factories, distribution and marketing - the pieces that actually unlock scale.

If you can point to a bottleneck and say, “Funding solves this and results in that”, your raise becomes ten times easier.

D) Make the opportunity easy to say yes to

W.K. de-risked his entire pitch before he ever entered a room. He had proven demand, predictable manufacturing costs, a scalable production method and a simple tweak - sugar - that expanded the total addressable market instantly. Investors weren’t taking a leap of faith; they were stepping onto a moving train.

Your job as a founder is similar: shrink the unknowns. The more you can make the upside feel obvious and the downside feel limited, the faster the “yes” arrives.

E) Be flexible enough to catch the opportunity in front of you

J.H.’s rigidity made sense within his worldview, but it also blinded him to a generational opportunity. W.K. wasn’t morally compromised; he was simply aligned with reality.

Markets evolve, cultural attitudes shift and customer behaviour changes long before founders want it to. The companies that thrive are the ones that stay grounded, not the ones that cling to an outdated version of what the business “should” be.

If you ask me, adaptability isn’t selling out; it’s staying relevant.

F) Prioritise consistency over fireworks

Kellogg’s didn’t scale like a TikTok sensation - no overnight explosions, no “you HAVE to try this cereal” influencer campaigns. Just 46 years of calm, steady growth before the IPO.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world is busy chasing virality on TikTok (I personally don’t have the time to doom scroll). However, quietly doing the same things well, over and over, still builds far more value than any short-lived spike.

G) Build a business an acquirer could integrate tomorrow

Kellogg’s ultimately sold for almost $40B because it was everything acquirers dream of: brand-rich, operationally clean and easy to plug into a much bigger machine. It wasn’t chaotic. It wasn’t founder-dependent. It was predictable, and predictability prints money.

Even if selling isn’t on your mind today, build like someone else might need to run your company tomorrow. Clean systems, organised operations and a brand with real meaning give you leverage long before you ever get an offer.

What is wrong with the world?!

That’s the book I’m reading at the moment, and it’s probably not the healthiest bedtime choice. It’s basically the literary equivalent of sitting next to someone on the bus who has very strong opinions about society, and you can’t decide whether they’re onto something or just sleep-deprived.

It covers everything - education, politics, marriage, economics and, funnily enough, sin - all delivered with the confidence of a man who never once questioned whether he might be wrong.

I’m about halfway through and still undecided.

How “sin” sneaks into financial decisions

All this talk of sin and morality got me thinking about how founders talk about money. Specifically, debt.

A lot of SMEs treat it as inherently “bad”; something you avoid unless absolutely necessary. I hear it a lot from SMEs who come to us at FundOnion.

But debt is a tool.

Sometimes it’s the smartest, cleanest way to unlock growth. Sometimes it’s the reason a business actually survives the next 12 months. And often, it’s far more efficient than stretching every pound until it snaps.

If you want help figuring out what the right funding tool looks like for your business, hit reply - always happy to talk it through.

Till next time,

James