Remember when contactless payments first arrived?

It felt revolutionary - borderline witchcraft, even. Suddenly you could just… tap something and money moved.

Now it’s so mundane that I genuinely couldn’t tell you my own PIN if my life depended on it.

Fast-forward to today and we’ve levelled up even further: Apple Pay, instant bill-splitting, sending someone money in the exact amount of 0.3 seconds… all completely normal.

We don’t even think about it. Digital banking is so smooth now it barely registers as technology anymore.

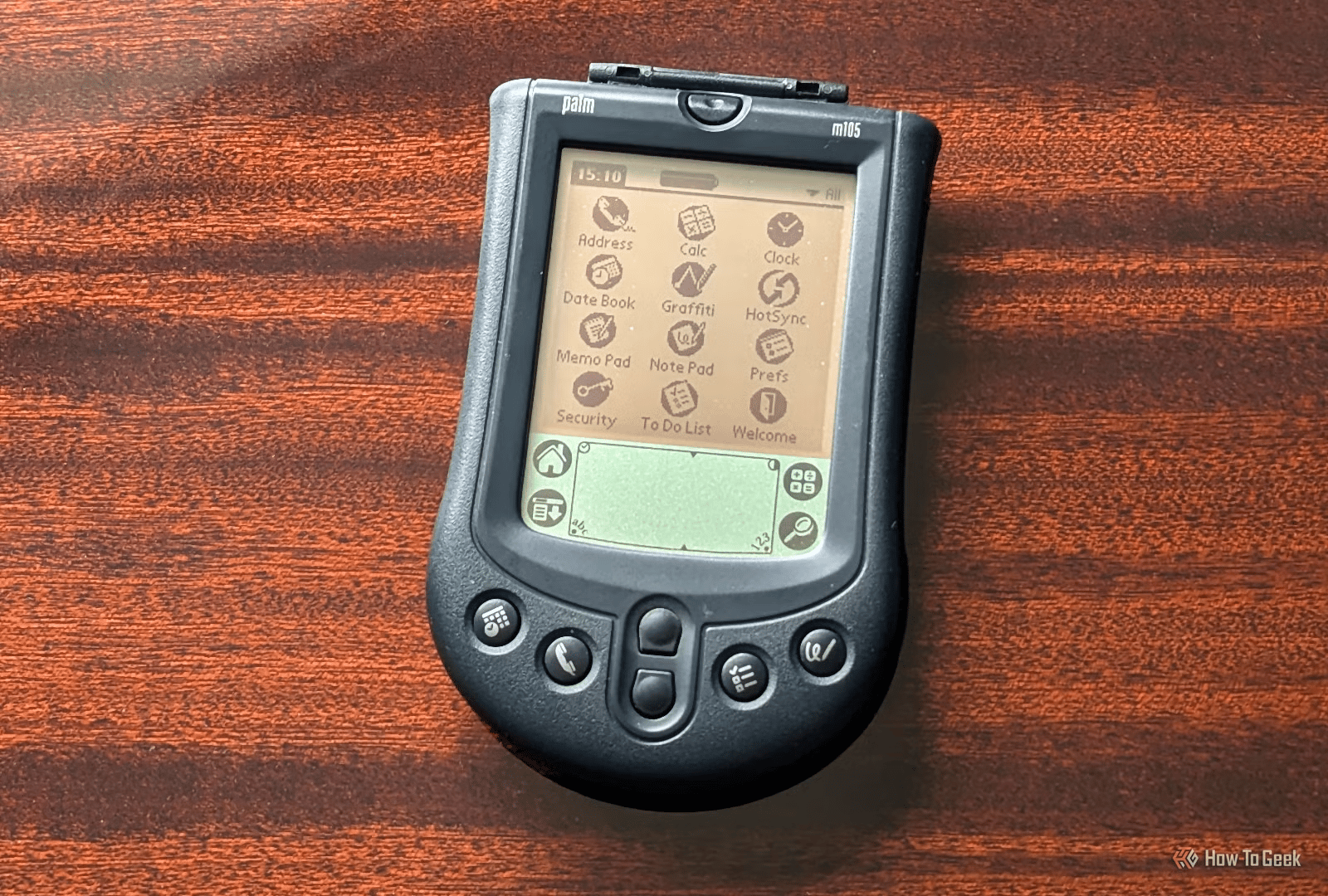

But all of this traces back to a tiny startup in the late 90s; a group of ambitious twenty-somethings who were tinkering with the earliest version of online payments. They weren’t trying to take over banking - they were simply trying to get Palm Pilots (the ancient ancestors of smartphones) to communicate.

That tiny startup was PayPal.

And while PayPal did eventually overhaul banking - dragging us out of the Dark Ages of cheques and clunky card readers - that’s not the part that interests me.

The part I care about is the fact that PayPal managed to raise $216M while being 67% dependent on a single customer.

Naturally, this begs the question: who was that customer? Keep scrolling to find out.

TL;DR

Short on time? I’ll share the key points here.

1/ Paypal’s original idea - Palm Pilot payments - went nowhere. But users started using the product in a completely different way: to pay for eBay auctions.

2/ They raised $216M while 67% reliant on eBay as their sole customer.

3/ That dependency was risky, but it gave PayPal exactly what early startups need: volume, data and real-world feedback.

4/ They used that momentum to raise aggressively and build world-class fraud + payments infrastructure before anyone else.

5/ eBay became both their biggest risk and their launchpad, eventually buying PayPal for $1.5B.

6/ PayPal later spun out, scaled globally and now powers modern digital payments (even partnering with OpenAI).

7/ Key SME lesson: relying on one customer can accelerate learning, but most businesses can’t absorb the downside. Show real demand - but don’t hinge your entire future on one client.

What do the founders of Tesla, YouTube and LinkedIn all have in common?

Besides more money than they know what to do with? They founded PayPal first.

Back in 1998, the company wasn’t even called PayPal - it was Confinity, and the grand vision was to create payment tools for Palm Pilots. These were small handheld devices that handled calendars, contacts and simple apps long before smartphones existed.

Unsurprisingly, the idea flopped. Hard.

Barely anyone owned Palm Pilots, and even fewer wanted to “beam” money between devices. The use case - quick digital payments between individuals - just wasn’t a real need yet.

But something interesting did happen

People started using Confinity’s web-based tool to settle eBay auctions. Completely organically. No push, no marketing, no strategy deck - just users doing whatever made their lives easier.

And by 2000, a ridiculous 67% of PayPal’s transactions were coming from eBay.

A dream and a nightmare rolled into one: massive dependency risk, but also an unexpectedly rich data pipeline.

Because while PayPal was clinging to one customer for survival, that one customer was giving them something priceless: millions of real transactions to learn from.

Fraud detection, chargebacks, instant transfers - PayPal accidentally became world-class at the hardest parts of moving money online. Exactly the capabilities the entire internet would soon need.

To stay ahead (and to build infrastructure strong enough that it didn’t collapse under eBay’s weight), PayPal started raising aggressively:

Feb 1999 - $0.5M

Aug 1999 - $4.5M (Nokia Ventures)

Jan 2000 - $12.9M (Sequoia)

Mar 2000 - $100M (Madison Dearborn)

Feb 2001 - $86.2M

A total of $216M, raised while still massively reliant on eBay.

That money went straight into the infrastructure that would eventually power the entire fintech industry: fraud systems, instant transfers, security protocols, everything.

And eBay? They became PayPal’s live testing environment - millions of messy, real-world transactions every single day. PayPal couldn’t have bought that kind of data even if they tried.

The results every founder dreams about

So where did things go after PayPal spent years depending almost entirely on eBay?

Straight into hyper-growth.

They went public in 2002.

Shortly after, eBay acquired them for $1.5B; a clear sign that PayPal had become mission-critical to the platform.

And by 2015, PayPal spun out again as a standalone public company, this time operating with the confidence of a business that categorically knew it didn’t need anyone else to survive.

Today, in 2025, PayPal sits at a $46B market cap and is partnering with OpenAI to power payments for the next wave of AI-driven commerce. Same strategy as the early days: become the infrastructure other people can’t live without.

And as for the founders who kicked all this off…

They took that momentum and ran with it:

Elon Musk went off to… do I really need to tell you what he’s been up to?!

Peter Thiel launched Palantir and wrote some of the earliest cheques into Facebook.

Reid Hoffman built LinkedIn.

Max Levchin founded Affirm.

And it keeps going: YouTube, Yelp, Yammer… the entire so-called PayPal Mafia essentially took over Silicon Valley.

The part that completely blows my mind, however, is:

If eBay users hadn’t hijacked PayPal as their go-to payment method - if eBay hadn’t become this incredibly loyal (borderline obsessive) customer - none of this might have happened. PayPal might still be sitting around trying to convince people to beam money between Palm Pilots.

Instead, that dependency became the rocket fuel - literally, in Musk’s case - and figuratively for the payments empire PayPal grew into. It also was the launchpad for the founders to create the tech giants we now take for granted.

A perfect example of the butterfly effect in action.

Modern fundraising lessons from a 90s startup

If they raised $216M off one customer, your raise is absolutely doable. Here are some of the insights I’ve pulled out of this case study:

1/ Use risk strategically

PayPal proves that concentration risk doesn’t mean future disaster. Having 67% of their business tied to eBay looked terrifying on paper, but it gave them exactly what early-stage companies usually lack: volume, behaviour data and constant feedback. That “risk” helped them improve the product far faster than if they’d tried to spread themselves across five different customer types.

LinkedIn agrees with me here:

Dependency wasn’t the problem - it was the accelerator.

If one customer segment is giving you momentum, lean into it instead of spreading yourself thin.

2/ Act fast

Momentum has an expiry date, however. If you wait for the “perfect moment”, you’ll usually find that someone else already shipped the thing you were still polishing.

PayPal understood that quicker than most. Their first product flopped, granted - but the second they noticed people using PayPal on eBay, they didn’t overthink it. They moved. Immediately.

They raised capital before anyone else had fully grasped what online payments were about to become. And that early raise is what let them build the infrastructure everyone else would later rely on. By the time competitors caught on, PayPal already had fraud protection, instant transfers and millions of real transactions to learn from.

So if you’re raising right now, take the hint: secure capital while you still have leverage. (And yes, FundOnion exists for exactly this reason.)

3/ Time it right

Speed is important, yes, but timing is paramount. PayPal built the right product at the exact moment the internet desperately needed it.

They launched during the Dot-Com bubble, when everyone was convinced the internet was going to change everything (incidentally, it did). Investors were throwing money at anything with a URL, and companies were racing to get online as fast as humanly possible.

Then the crash hit.

The hype died down.

The weak companies evaporated.

PayPal weathered the storm though - the online companies that survived still needed a way to process online payments.

Timing + readiness = unfair advantage.

4/ Solve real pain points

PayPal won because they solved a problem everyone else was struggling with: moving money online quickly and safely. That was the single biggest friction point for early ecommerce, and PayPal made it effortless.

They focused on one core job and executed it exceptionally well - fraud handling, chargebacks and instant transfers became their signature strengths. Once they nailed that, the rest of the growth followed naturally.

When you solve a painful, universal problem better than anyone else, you don’t need to do much else. The market comes to you.

5/ Build mutually beneficial partnerships

eBay needed a payment system people actually trusted. PayPal needed users - lots of them, quickly. The partnership unlocked scale for both sides.

eBay got a smoother checkout experience. PayPal got millions of transactions and instant credibility. That flywheel is what pushed PayPal from ‘startup experiment’ to the default way to pay online.

And they never stopped using that strategy. After eBay came Shopify, marketplaces, platforms… and now OpenAI.

The pattern is pretty clear: partnerships grow you faster than trying to do everything alone.

6/ Know when to part ways

Of course, not every partnership is meant to last forever. After more than a decade of powering eBay’s payments, PayPal eventually outgrew the relationship.

eBay wanted to double down on its marketplace.

PayPal wanted to become everyone’s payment infrastructure, not just eBay’s.

So in 2015, they split - not because anyone wronged anyone, but simply because the relationship had run its course.

Very mature, unlike most breakups.

And that’s a useful reminder for SMEs: loyalty is great, but not when it traps you in a partnership you’ve outgrown. Progress sometimes requires politely stepping out of what used to work.

7/ Keep innovating

PayPal started in the 90s.

So did MSN, Tamagotchis and dial-up internet. Yet somehow PayPal is the only one still going - because it never stopped innovating.

In 2013, PayPal acquired Venmo because younger users were flocking to it for quick, social, emoji-filled payments; the opposite of PayPal’s more “sensible adult” approach. It was the smartest way to stay relevant to the next generation without trying to reinvent itself from scratch.

And now? They’re partnering with OpenAI, positioning themselves as the payment rails for whatever the AI economy becomes.

Same pattern as always: get ahead early, buy or partner with what’s next and give competitors something to chase.

My point? Never stop learning, tweaking, adapting, evolving.

On a more personal note:

I’m back in London after a three-week trip through Vietnam and Australia, easing back into work and mourning the loss of Aussie sunshine.

It was meant to be a full switch-off, but I found myself thinking about work (more specifically, how we make payments). Tapping my card for street food in Vietnam, splitting brunch in Sydney with a quick transfer - same motions, totally different places.

It’s only when you travel like that that you realise how global this stuff really is. And how much of it traces back to the early work done by the PayPal founders.

What you can (and can’t) take from PayPal’s playbook

PayPal took a big gamble by relying on one major customer early on. It only worked because they grew fast enough to reduce that risk. Most SMEs don’t have that luxury - if one customer disappears, the whole business can wobble.

So here’s the takeaway:

Show real demand by proving people actually use and pay for your product - but don’t rely on one customer to hold everything up. Spread the risk, grow steadily and raise money to strengthen what’s already working, not to patch over weaknesses.

If you’d prefer not to gamble your raise on “hopefully that one customer sticks around” I can help you build something sturdier. Just hit reply

Till next time,

James