Coffee’s been a ritual for centuries. People wake up, grab one, maybe two more before noon. It’s an addiction we’ve all agreed to enable.

You know what else runs on the same logic? Netflix. A small monthly fee, endless “refills” of something that keeps you coming back.

And in 2020, Pret drew a parallel - turning your caffeine habit into a membership.

It couldn’t have come at a better time. The pandemic nearly broke them. Offices were empty, footfall collapsed and a business built on commuters was suddenly irrelevant.

To survive, Pret launched ‘Club Pret’ - a £20-a-month coffee subscription. Marketed as all-you-can-drink, capped at five cups a day, it was outrageously good value. Anyone doing the maths realised you could hit breakeven by Wednesday and drink for free the rest of the month.

Within months, 1.4 million people had signed up. Those subscribers were reported to spend around four times more than non-members. For JAB, the private equity firm that bought Pret for £1.5bn in 2018 (and pumped in another £250m when things went south in 2022), that subscription became the centrepiece of a planned £2bn+ IPO.

So, what got investors hooked? Not the copious amounts of caffeine, but the data, predictability and proof that commitment-based pricing can scale in physical retail.

This week, I’ll break down:

How Pret turned a pandemic subscription gimmick into a multibillion-pound asset

Why investors prize predictability, despite lack of profits

What lenders look at when you try to raise against recurring revenue

The hidden risks that could still unravel Pret’s carefully brewed model

Free coffee, expensive habits

Netflix turned bingeing into a business model. Pret did the same with caffeine. £20 a month for up to five coffees a day looks almost charitable, but really it’s an invisible turnstile.

Once you’ve paid, you want to get your money’s worth - so you stop by more often. And while you’re there, that “free” flat white usually comes with a £5 sandwich. Do that twenty times a month and you’ve doubled your spend.

That pattern was the real breakthrough. Pret didn’t just sell coffee; they engineered routine. A million subscribers now walk through the door several times a week, each transaction logged, timed and stored - evidence that gives investors what they crave most: predictability.

That’s what JAB is really preparing to float. Not a coffee chain, but proof that behaviour can be manufactured at scale. Klarna did it with “buy now, pay later”. Pret did it with caffeine on tap. Both turned habits into billion-pound valuations.

And beneath it all lies the real currency: data. Every tap of a card, every extra croissant adds another entry to a behavioural goldmine. A commenter on my LinkedIn post called it a data jackpot - and they’re right.

Still, even a jackpot needs funding. At Pret, that bill lands with the walk-in crowd.

Subscribers leave smiling with their bargain cappuccinos (and perhaps an extra croissant in hand).

Non-subscribers (i.e. casual Pret customers) unknowingly fund the scheme through higher menu prices.

It’s a neat inversion → Loyalty earns discounts, indifference gets taxed.

Piece all this together, and you can see that Pret has been running a psychology experiment in plain sight. Every swipe is proof that commitment beats loyalty cards. And if you think you’re choosing freely by queuing for your ‘discounted’ flat white, you’re already part of the experiment.

What a Starbuck’s loyalist thinks about Pret

The most overlooked part of Pret’s subscription isn’t the marketing, it’s the financing impact. Before Club Pret, their revenue rose and fell with the morning rush. Some days were packed, others painfully quiet.

The subscription changed that. Suddenly, Pret had money coming in every month, no matter how many people walked through the door. It’s not as predictable as a software company charging by direct debit, but it’s far more reliable than walk-in trade.

And that matters for one reason: it changes how lenders see you.

An IPO raises belief - it tells the market you’re credible, established and worth backing. Debt raises consistency, as it reassures lenders that money comes in as planned (not in sporadic bursts). Instead of volatile lunch-hour spikes, Pret could suddenly point to revenue that was rhythmic, reliable and safe to lend against. At their size, that means bonds. At a smaller scale, it would mean revenue-based loans tied directly to subscription income. The same principle can apply to a different bracket.

The point I’m trying to make here is, if money comes in on schedule, you can borrow against it. And while you may not run a subscription-based business, there are plenty of ways to strengthen cash flow that lenders value (I’ve outlined some practical strategies for you to read here).

To a lender, “predictable cash flow” is just the start. They’ll want the receipts too, which will look something like:

a) Renewal rates: do customers stick after the first month’s novelty?

b) Sentiment: do they actually like it, or just tolerate it?

c) Macro conditions: are wages, inflation or consumer habits about to knock it sideways?

Once those boxes are ticked, the formula is simple:

Predictable Income + Manageable Churn =

Confidence To Lend (and margin to price risk)

And that’s where Pret lands today.

1/ On the confidence side, they’ve got a global footprint locked in with long leases, margins that hold up against peers and millions of subscribers whose routines are consistent enough to forecast.

2/ On the risk side, labour costs are rising faster than coffee prices - UK hospitality wages have been climbing above inflation - and Pret can’t automate much more without looking like a vending machine chain.

3/ For lenders, that balance is the make-or-break factor: predictable inflows on one hand, cost pressure on the other. As long as the first outweighs the second, Pret can borrow against coffee habits all day long.

Takeaways from Pret (not the sandwich kind)

Some snackable insights for SMEs raising capital:

A) Prioritise predictability

Cash flow is the only number that counts when lenders size you up. Not your glossy profit margins. Not your vanity revenue spikes. They’re asking: how certain is the next £10k coming in? The more regular and reliable, the stronger your hand when you need capital.

B) Lock in behaviour, not just sales

One-off transactions don’t impress investors. Systems that get customers to repeat - almost without thinking - do. That’s what subscriptions, retainers and long-term contracts really are: financial flywheels. Build them early, and you can negotiate debt on your own terms.

C) Smooth the spikes

Big wins look great online, but lenders hate unpredictable cash flow. If your income swings wildly from one month to the next, it signals risk. Spread payments out where you can, set up regular billing and avoid relying on one huge contract that leaves you quiet the rest of the quarter. Stability might look dull, but it’s what lenders trust.

D) Price with psychology

Discounts aren’t discounts if they train customers to spend more. Think in triggers, anchors and identities: what pulls people in, what upsells them and what makes them stick around. Done right, the “loss leader” becomes leverage.

⚠️ Warning for founders: Recurring revenue isn’t a free pass. Subscriptions only build confidence if churn stays low and loyalty is real. Push too hard or stop delivering value, and the steady income you thought you could borrow against turns fragile overnight.

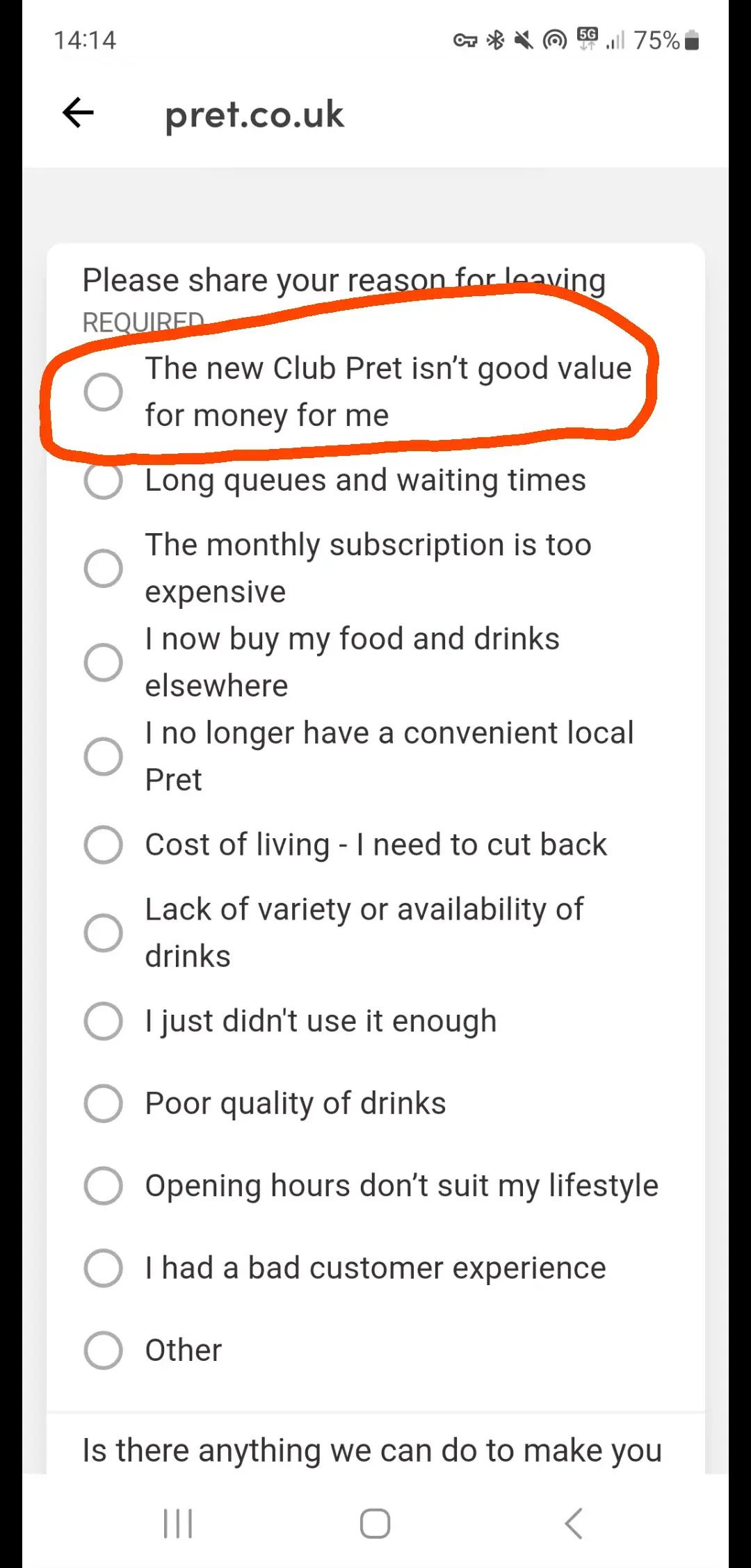

Pret avoided that trap (for now). You can’t freeze a £20 subscription forever while costs rise and habits evolve. The “all-you-can-drink” phase hooked customers; now the model’s been fine-tuned: £20 became £25, then £30 and now it’s £5 a month for 50% off up to five barista-made drinks a day. A more sustainable offer that keeps both the margins and the loyalty alive.

It’s clearly working for them, but at this point, I’ve lost track of how much a cup of coffee costs…

TL;DR:

A) Pret proved that subscriptions aren’t gimmicks; they’re a way to turn customer habits into steady, predictable cash flow.

B) That consistency made the business easier to fund. When revenue comes in regularly, lenders see collateral, not risk.

C) They’re reassured by stable margins, loyal customers and long leases - but rising labour costs and limited automation still raise eyebrows.

D) For smaller businesses, reliable cash flow matters more than high profits on paper. It’s what keeps funding options open when growth gets expensive.

E) Build real loyalty and commitment into your model, and you’ll have something investors - and lenders - can trust.

Quick (but relevant) side note

One of my idols is David Goggins. The man runs ultramarathons for fun, screams at himself in the mirror and generally makes the rest of us look like amateurs. I’m not about to run a hundred miles in the desert (or am I), but the point I’m trying to make is: resilience beats glamour.

Business is the same. Everyone loves the IPO headline. No one wants the grind of cash flow forecasts, debt repayments or the dull discipline that actually keeps your business going. The founders who succeed are the ones willing to keep plodding along, even when it’s boring (or painful).

Get your caffeine-free clarity here

I’ve recently switched to decaf and honestly - life changing. Clearer head, fewer jitters and better sleep. Turns out I didn’t need caffeine to function.

Pret, on the other hand, did. Or so we thought. Sixty-three million coffees later, it’s clear the real buzz wasn’t from espresso - it was from consistent cash flow. That’s what investors paid billions for. That’s what lenders back. And without it, you’re just another café waiting for a morning rush that never comes.

So before you get back in the funding queue, ask yourself: are you running on hype, or on steady inflows you can actually borrow against?

If it’s the latter, I can help. Just reply to this email - or fill in this short form - and me (or someone from my team) will be in touch to explore your funding options.

Till next time,

James